Chapter 1: Boxer War

The March of Time - 20th Century History

With a PoD in Boxer Rebellion, this TL focuses on the major geopolitical events of the 20th century.

The rise of the Boxer movement

By the beginning of the century, tensions within the Chinese society were reaching a boiling point. After a century of humiliating defeats at the hands of pagan barbarians, the ruling Chi'ing dynasty of the Middle Kingdom had at first witnessed a frantic Westernization program, followed by an internal power struggle where the supporters of reform had been soundly defeated by the arch-conservative Manchu Empress Dowager and her henchmen. While the court schemed and pondered the direction the country should take in the face of Western imperialism, renewed and increased contact with the outside world had shocking and rapid effects to living conditions of the common people.

First the British had gone to war to keep their lucrative opium markets open, and humiliated the obsolete Chinese navy. The following decades had marked a trend where foreigners had been in a position to dictate trade terms that had forcibly ruined Chinese protective tariffs and allowed their domestic markets to be flooded with cheap imports. By the first year of the 20th century, the once flourishing village industries were virtually bankrupt in the face of this foreign competition.

The arrival of foreigners had also brought railroads to compete with the ancient communication and trade routes within the vast Empire. For centuries, the Grand Canal had been the life-vein through which the southern tribute rice had been commuted to the northern China. Now both the Canal and the old Hankow-Peking trade road had both been rendered obsolete by the new railroads, and countless cart drivers, bargemen, innkeepers and rice traders had suddenly found their livelihoods ruined by this foreign invention. To make matters worse these changes had greatly imbalanced the imperial budget. When the growing trade deficit forced the imperial government to raise taxes, dissent among the population soared.

Economy was one thing, but the foreigners were also blamed for the devastation brought along by the Taiping rebels. Even after millions had died and vast areas of China had been ruined to starvation and famine in this bloody and failed revolt, the very same foreign missionaries who had stirred the rebellion in the first place by their alien barbarian religion were now allowed to openly lure Chinese people to their new cult. For many it was easy to link this sacrilege to the troubles and natural disasters that had plagued China in the last years. By the beginning of the century the flooding of the mighty Yellow River had caused widespread destruction, after which severe drought had destroyed crops in Northern China. Hunger was by then nothing new in the Chinese countryside, as the destruction and famines brought along by the Taiping rebellion were within living memory. The previous hardships had already turned the countryside restless, and many villages and towns were already teeming with vagrants and bandits.

When driven to such situation, the people were eager to listen anyone who offered them easy explanations and scapegoats to their problem. The arrogant Westerners were an easy and logical target. Ridding China from their evil influence would surely bring back the natural order of things and restore life to the peaceful and good state of the golden past. It was thus no wonder that the supporters of the Righteous and Harmonious Fists was able to recruit so many Chinese to their superstitious antiforeign movement. The "Boxers", as the members of the movement were later on known in the West due their calisthenic combat rituals, initially sought to both rid China of foreigners and spoke of slaying "one dragon, two tigers and three hundred lambs." In this they were loyal to their anti-dynastic secret society roots and referred to the reform-minded Manchu Emperor Kuang-hsü, and the two Manchu princes and all metropolitan officials who had been contaminated by foreign contact. Despite this initial streak in their ideology, the Boxer movement was ultimately steered towards grimly summarized policy: "support Chi'ing and exterminate the foreigners."

This was largely achieved by the actions of few key officials, especially Yü-hsien, the new governor of Shantung province. After the had openly subsidized the movement and helped it spread despite foreign protests, he was finally summoned to the court to explain his actions. There he managed to portray his policies to the reactionary Manchu princes and officials as beneficial development, and they in turn convinced the Empress Dowager to consider the idea of using the movement to "drive the foreigners away." Gradually the Imperial Woman who was rather uninformed of the rapidly changing outside world due her isolated life in the court was swayed to the viewpoint of these anti-foreign reactionaries, who were equally blind to the geopolitical situation of China. Daily they kept telling her that the Boxers were favoured by the gods and immune to bullets and were thus the right force to restore the dignity of China and expel the troublesome barbarians. The court and Empress Dowager did not change their mind overnight, but gradually the Boxer movement gained more support. In the spring of 1900 groups of Boxers, know calling themselves Righteous and Harmonious Militia, were openly attacking symbols of foreign enslavement. They damaged and destroyed telegraph lines and railways, fully aware that the back in the capitol princes and nobles were now setting up tables to burn incense to their gods, while regular government troops were joining to the ranks of their movement.

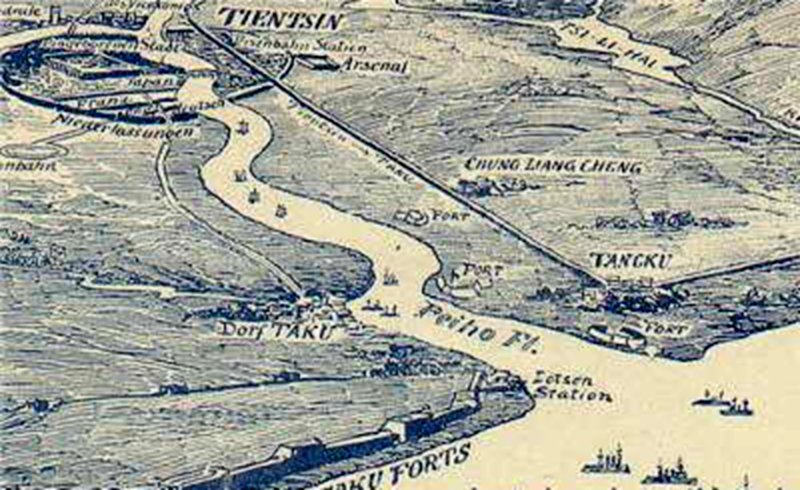

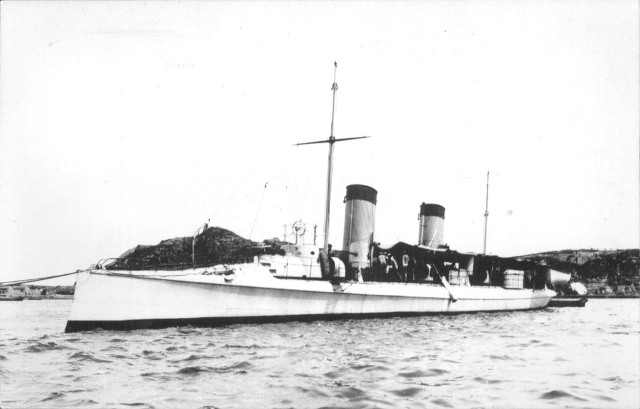

Alerted by the deteriorating situation, the foreign diplomatic community in Peking called in more guards from Tientsin harbor. Soon thereafter the Boxers cut the railway the railway between Peking and Tientsin, and more and more Boxers begun to gather to northern China. Now truly alarmed by the quickly deteriorating situation, the foreign legations wired an urgent request of help and reinforcements to the coast. British Admiral Seymour started to move inland with his 2100 men strong multinational force by 10th of June, and soon thereafter contact to Peking was lost as the last telegraph lines were cut. Now no one in the West really knew what was happening in the Chinese capital, but events in Tientsin made foreign governments fear for the safety of their citizens and legates in Peking. By June Boxer groups were roaming in Tientsin virtually unopposed, and they set the streets ablaze. Foreign merchandise and books were burned alongside churches. Christians, missionaries and Chinese converts alike, were hunted and put to death when captured. After the Boxers broke in prison and looted the local government arsenal, the captains of foreign vessels anchored at the outskirts of Taku Forts gathered to an emergency meeting to discuss their options.

With a PoD in Boxer Rebellion, this TL focuses on the major geopolitical events of the 20th century.

The rise of the Boxer movement

By the beginning of the century, tensions within the Chinese society were reaching a boiling point. After a century of humiliating defeats at the hands of pagan barbarians, the ruling Chi'ing dynasty of the Middle Kingdom had at first witnessed a frantic Westernization program, followed by an internal power struggle where the supporters of reform had been soundly defeated by the arch-conservative Manchu Empress Dowager and her henchmen. While the court schemed and pondered the direction the country should take in the face of Western imperialism, renewed and increased contact with the outside world had shocking and rapid effects to living conditions of the common people.

First the British had gone to war to keep their lucrative opium markets open, and humiliated the obsolete Chinese navy. The following decades had marked a trend where foreigners had been in a position to dictate trade terms that had forcibly ruined Chinese protective tariffs and allowed their domestic markets to be flooded with cheap imports. By the first year of the 20th century, the once flourishing village industries were virtually bankrupt in the face of this foreign competition.

The arrival of foreigners had also brought railroads to compete with the ancient communication and trade routes within the vast Empire. For centuries, the Grand Canal had been the life-vein through which the southern tribute rice had been commuted to the northern China. Now both the Canal and the old Hankow-Peking trade road had both been rendered obsolete by the new railroads, and countless cart drivers, bargemen, innkeepers and rice traders had suddenly found their livelihoods ruined by this foreign invention. To make matters worse these changes had greatly imbalanced the imperial budget. When the growing trade deficit forced the imperial government to raise taxes, dissent among the population soared.

Economy was one thing, but the foreigners were also blamed for the devastation brought along by the Taiping rebels. Even after millions had died and vast areas of China had been ruined to starvation and famine in this bloody and failed revolt, the very same foreign missionaries who had stirred the rebellion in the first place by their alien barbarian religion were now allowed to openly lure Chinese people to their new cult. For many it was easy to link this sacrilege to the troubles and natural disasters that had plagued China in the last years. By the beginning of the century the flooding of the mighty Yellow River had caused widespread destruction, after which severe drought had destroyed crops in Northern China. Hunger was by then nothing new in the Chinese countryside, as the destruction and famines brought along by the Taiping rebellion were within living memory. The previous hardships had already turned the countryside restless, and many villages and towns were already teeming with vagrants and bandits.

When driven to such situation, the people were eager to listen anyone who offered them easy explanations and scapegoats to their problem. The arrogant Westerners were an easy and logical target. Ridding China from their evil influence would surely bring back the natural order of things and restore life to the peaceful and good state of the golden past. It was thus no wonder that the supporters of the Righteous and Harmonious Fists was able to recruit so many Chinese to their superstitious antiforeign movement. The "Boxers", as the members of the movement were later on known in the West due their calisthenic combat rituals, initially sought to both rid China of foreigners and spoke of slaying "one dragon, two tigers and three hundred lambs." In this they were loyal to their anti-dynastic secret society roots and referred to the reform-minded Manchu Emperor Kuang-hsü, and the two Manchu princes and all metropolitan officials who had been contaminated by foreign contact. Despite this initial streak in their ideology, the Boxer movement was ultimately steered towards grimly summarized policy: "support Chi'ing and exterminate the foreigners."

This was largely achieved by the actions of few key officials, especially Yü-hsien, the new governor of Shantung province. After the had openly subsidized the movement and helped it spread despite foreign protests, he was finally summoned to the court to explain his actions. There he managed to portray his policies to the reactionary Manchu princes and officials as beneficial development, and they in turn convinced the Empress Dowager to consider the idea of using the movement to "drive the foreigners away." Gradually the Imperial Woman who was rather uninformed of the rapidly changing outside world due her isolated life in the court was swayed to the viewpoint of these anti-foreign reactionaries, who were equally blind to the geopolitical situation of China. Daily they kept telling her that the Boxers were favoured by the gods and immune to bullets and were thus the right force to restore the dignity of China and expel the troublesome barbarians. The court and Empress Dowager did not change their mind overnight, but gradually the Boxer movement gained more support. In the spring of 1900 groups of Boxers, know calling themselves Righteous and Harmonious Militia, were openly attacking symbols of foreign enslavement. They damaged and destroyed telegraph lines and railways, fully aware that the back in the capitol princes and nobles were now setting up tables to burn incense to their gods, while regular government troops were joining to the ranks of their movement.

Alerted by the deteriorating situation, the foreign diplomatic community in Peking called in more guards from Tientsin harbor. Soon thereafter the Boxers cut the railway the railway between Peking and Tientsin, and more and more Boxers begun to gather to northern China. Now truly alarmed by the quickly deteriorating situation, the foreign legations wired an urgent request of help and reinforcements to the coast. British Admiral Seymour started to move inland with his 2100 men strong multinational force by 10th of June, and soon thereafter contact to Peking was lost as the last telegraph lines were cut. Now no one in the West really knew what was happening in the Chinese capital, but events in Tientsin made foreign governments fear for the safety of their citizens and legates in Peking. By June Boxer groups were roaming in Tientsin virtually unopposed, and they set the streets ablaze. Foreign merchandise and books were burned alongside churches. Christians, missionaries and Chinese converts alike, were hunted and put to death when captured. After the Boxers broke in prison and looted the local government arsenal, the captains of foreign vessels anchored at the outskirts of Taku Forts gathered to an emergency meeting to discuss their options.

Last edited: