A Crippled History of New England

by Marianne Bottler

~ Preface ~

by Marianne Bottler

~ Preface ~

– Blake Baldwin, from the March 2012 issue of Philadelphia Whig“…Ms. Bottler’s work is a sore on the face of Yankee literature. She is a deformed husk of old movements limping into the present day, a moral cripple, as much a wolf in sheep’s clothing as her father. Her books are more than a waste of time; they are an active drain on all that is right and proper in this world.”

I’m as surprised as you are to see a history book with my name on the cover. History and politics have always been my father’s domain. I’ve lived in my own world since I was a little girl. I remember Daddy came home from a Senate meeting late one night reeking of coffee, his collar stained, his eyes bloodshot and baggy. I swallowed the remains of his coffee that morning, always black and bitter. I wanted to drink like a grown-up, and I was still feeling the effects. He walked into my bedroom and found me lying on my stomach in bed, my lips pulled back into a crocodile grin, flapping my arms with crutches in hand. I was shocked to see him. “Daddy!” I gasped. “How’d you get all the way up in the air?” I’d been imagining myself as one of those World War bombers with the shark teeth painted on the nose. I always wanted to walk like a normal kid, like the ones who liked to make fun of me. To fly would be something else. The Big Bottler smiled, strapped on a pair of invisible goggles, and gave me a thumbs up. “Room up there for two?” he said. Daddy never managed to understand me, but he was always willing to spend time in someone else’s world. It’s a quality I still envy in him. He left the creative stuff to me until the last few years of his life. He hated an idle mind. He needed a way to occupy himself when the cancer took him out of politics. I was the one who suggested he take up the new family business. He wasn’t much good, to be honest, mostly heavy-handed poetry, but he loved to read them to me. He’d write in the margins of the newspaper, next to his half-completed crossword puzzles. Now he’s gone, and here I am with all of his history books on my desk.

Now, I’m the first to admit that I have a flexible version of history. If you want a reliable narrator, there are plenty of history books written by real historians. You can flip to the bibliography and use it as a reading list. You can use the rest to line a birdcage or stoke a fire. Get creative. I know some of you took umbrage with my last book. Is it ridiculous to suggest that the survival of one man could unite such different cultures and stretch the United States to the Pacific coast? Absolutely. Welcome to satire. If you’re offended, it means my publisher won’t fire me this year, those poor naïve fools. I find it ridiculous that, even in the 21st century, the very idea that Yankees and Americans could compromise and reconcile themselves to co-existence is so hard to swallow. I don’t think it could happen, but it’s an interesting idea to explore. The point of fiction is to put a carnival mirror before our own experience, and all writing is fiction – even history. Before we move on, I’d like to add that the purpose of the book was not to posit an alternate history. The fact that it took place in alternate world was incidental, and if you actually read the damn thing you’d understand that. I’d say I’m shocked that a work of speculative fiction could invite such ire, but I’d be lying to you. I’m not a reliable narrator, but I’m a professional liar, as are all writers and politicians. I suppose in that sense, I follow in my father’s footsteps. I play fast and loose with the rules. I’m too cool for school. Deal with it, Baldwin.

~ ~ ~

Chapter One: Cain and Abel

The Birth of Twin Nations

Chapter One: Cain and Abel

The Birth of Twin Nations

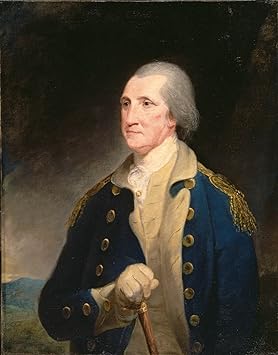

George Washington’s “martyrdom” during the Siege of Yorktown on October 4th, 1781 is the subject of much debate, most significantly by me in my last novel. His death is one of the freak accidents that define our country’s history. In Another Country, I describe the altered trajectory that changes the world from the voice of Israel Evans, chaplain of the Continental Army:

… After I led the men in prayer, Washington came home from the redoubts late last night. He crept back into camp in burglar black. He woke me at the crack of dawn to dig our positions, and I thought I caught a certain youthful glimmer behind his determination. He must’ve missed scouting. I wonder if he felt like he did in the Seven Years War, his old days. Washington had a shovel in hand even with Cornwallis’s occasional artillery. The lobsterback sulked in Yorktown like a wounded lion in cave, or a coiled serpent. Cornered animals are the most dangerous.

We walked along the battlements, preoccupied by private conversation. We heard a whistle, but we hardly had enough time to be surprised before the impact. A cannonball streaked from the sky like a lightning bolt from Heaven. Sand sprayed before my eyes, and time seemed to stand still. I wondered if this was the end of my life drawn out by God’s excruciating grace. General Washington stood in front of me, his shoulders tense, legs ready to leap, spine stiff in shock. The sound of the sand came so slow it seemed like the churning tide or the empty innards of a seashell, almost calming. The trees around us leaned back in shock. I gasped and took a few steps backward, my heart pounding. I looked down at my feet and wriggled my toes. Still alive. I looked over at the cannonball resting several feet away from us. When it wasn’t flying from a cannon, it had a lot less menace. I looked back up at the General and my hands went to my hat by instinct to dust it off. Washington stayed my hand with the hint of a chuckle. “Mr. Evans,” he said, “you must carry that home and show it to your wife and children.” I eked out a nervous smile.

I would hope that all my readers know what happened in our own history. In case anyone dropped out of secondary school but for some inconceivable reason still reads my books, I’d hate to disappoint. In our history, of course, that cannonball struck General George Washington dead. As the story goes, the only part of poor Mr. Evans left untouched by blood was his hat. At least that’s how I like to tell it.

The forces of liberty were only emboldened by their grief. Washington’s death mere days before the final offensive of the war would not blunt the assault, and Cornwallis surrendered on October 19th, 1781. The Americans won their war for independence, but Washington’s death fed into the desperation that came with cleaning up after a war. The soldiers were long unpaid and the lands neglected. Panic gripped the Thirteen Colonies. The end was in sight, but still out of grasp until the diplomats emerged from their peace talks. The General had been someone to rally around. Now he was gone, and he left a vacuum in his place. In 1783, a conspiratorial letter made its rounds around the camp at Newburgh. Soldiers in the Continental Army were tired of the Congress sitting on their hands while they fought for nothing. Many founding fathers of the American nations argued to the Congress in favor of at least partial compensation, including Alexander Hamilton. The members of the Newburgh Plot planned to overthrow the Congress in a second rebellion. Popular myth says they planned to establish a military government. It’s not impossible, but there’s no definitive proof they sought anything but immediate compensation at the barrel of a musket. As for myself, I prefer to believe the more interesting myth. In any case, Hamilton, who commanded troops and won glory in the Battle of Yorktown, announced that he’d speak with the discontented soldiers at a meeting in Newburgh. The plotters assumed Hamilton would lead them in insurrection. He was a charismatic young soldier himself, an up-and-comer, and Washington’s protégé. He’d exchanged letters with many of the leaders (such as Lewis Nicola) that seemed to support their radical ideas. When Hamilton reached his pulpit, he came prepared with more than a speech. He pulled a pair of Washington’s wooden teeth from his coat, held them aloft, and with all the fervor of an evangelist, he extolled their bravery and the bravery of their great leader, who had given his life for liberty. “If we sacrifice this great man’s gift today,” he said, “we sacrifice our souls!” Not everyone bought what Hamilton was selling, but enough of them did, and the rest could tell which way the wind was blowing. Some of them realized that Hamilton had added fuel to the fire to win prestige by putting it out, but it was too late and there was little evidence of his politicking.

Soon after the Newburgh Plot dispersed, Alexander Hamilton and Henry Knox founded the Society of the Cincinnati, an international organization for veterans who fought the British in the Revolutionary War. Hamilton was elected the Society’s first President. By the end of the year, the Treaty of Paris ended the war and the Thirteen Colonies won their independence. Even after the Treaty, fear continued to spread throughout the newly-sovereign states. They won the war, but they were already losing the peace. A thousand issues remained unresolved, from land speculation to war debts to native relations. The Articles of Confederation were rusting before their eyes, quickly proving an untenable document to bind the colonies together. New England in particular was terrified. Though the Newburgh Plot didn’t erupt into a coup, the memory still hung over the population of the Northern states. They knew they couldn’t protect themselves from external threats if they couldn’t bandage their own bleeding political body. The veterans received some amount of payment from the Congress after the close call at Newburgh, but it hardly seemed enough. Taxes were high in Massachusetts, and many farmers who fought in the war felt they’d fought against unfair taxation only to be taxed out of house and home again. After years of resistance to tax collectors, conflict bubbled to the surface with Shays’ Rebellion in 1786. Twenty leaders commanded almost 2,000 disgruntled veterans, most prominent among them Daniel Shays, though they called themselves the Regulators. After a bit of maneuvering and a string of both organized and disorganized shakedowns of tax collection offices, the Shaysites marshalled their troops and seized the federal armory at Springfield in January 1787, after a brief siege. They armed themselves to the teeth and massed in Springfield before marching on Boston and laying siege. Federal forces scrambled ineffectually to funnel troops from across the colonies. Southern states in particular had little desire to reward what they considered the tyranny of a Northern state. The Congress managed to bolster Massachusetts’ defenses in Boston to some degree, and Hamilton led an army of volunteers from the Society of the Cincinnati. On March 2nd, 1787, the rebels attacked the Federal forces at Boston. After a tumultuous battle, the defenders of Boston scattered the Regulators and broke the back of their rebellion.

The Massachusetts militia dealt with what Shaysites remained over the course of the year as the Federalist Papers began to circle the colonies, a number of ongoing essays in favor of a revised constitution and stronger, more centralized government. They were authored under pseudonyms by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and the Virginian James Madison. Other pre-eminent thinkers opposed to the Federalists such as George Clinton, Robert Yates, and Patrick Henry published their own papers in an ongoing debate. That debate would only escalate with the First Philadelphia Convention in 1788. The Convention was nominally convened to revise the Articles of Confederation, but its true intent was to replace them with a new Constitution. The secrecy of the Convention only added to public suspicion, especially in the Southern states, which felt increasingly estranged from New England’s problems and policies in the post-war era. Hamilton’s influence also soured the Convention’s reputation. Hamilton had many supporters, but he had a gift for making enemies. Thomas Jefferson had been appointed Minister to France by the Congress in 1785. After his wife’s death in childbirth in 1782, so soon after Washington’s, Jefferson was distraught, and many of his compatriots feared for his sanity and even his life. They felt that his time in France would take his mind off of the troubles at home, and for a time they did, but his friend James Monroe sent him a letter warning him of Hamilton’s many power grabs and hints of the Philadelphia Convention during its preliminary planning stages. Jefferson resigned his post and returned to the former colonies, though he was not invited to the Convention.

John Jay was elected President of the First Philadelphia Convention. His mild manner won him many friends, but he failed to be the moderating influence he was intended for. Hamilton’s ideas dominated the debate, but they also polarized it, and the atmosphere was bitterly divided for several months. Hamilton raised several points against slavery and against a Bill of Rights that alienated many anti-Federalists and even many Southern Federalists who otherwise supported his program. After four months, a number of Southern delegates left the Convention. Others followed suit over the course of the next week, and the Convention officially dissolved. Hamilton’s vitriol during the Convention also ruined his relationship with his former colleague, James Madison. Hamilton’s fury with his rivals would only increase by the end of the year. Jefferson and Madison organized the Richmond Convention and invited the states of Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Delaware, to send delegates and create a union based on “the true principles of a democratic republic.” Hamilton threw his energy into organizing the Second Philadelphia Convention and invited the states of Delaware, Philadelphia, New Jersey, New York, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Vermont, and New Hampshire. Delaware was the only state to be invited to both Conventions, but in the end, it declined to send delegates to Richmond and sent them back to Philadelphia instead. Though Delaware was torn between North and South in many ways, it had a mercantile economy and a Quaker foundation. Rhode Island and Vermont declined to send any delegates, but the other states accepted their respective invitations and the twin Conventions assembled in a race to union. This time, neither North nor South, Federalist nor Anti-Federalist, would be forced to compromise.

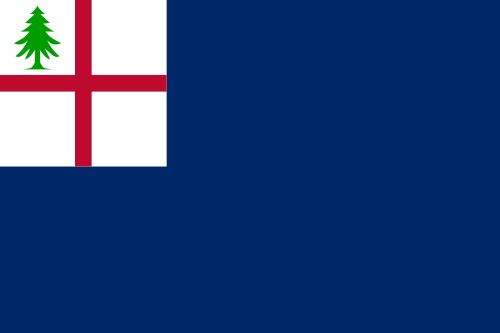

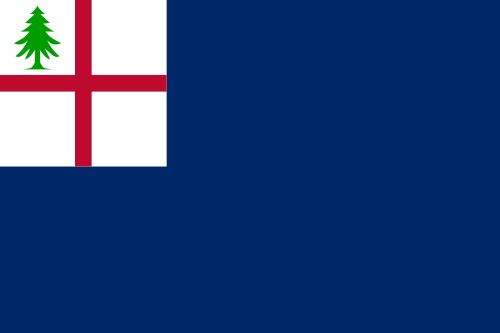

EDITOR: Enjoy my terrible map of New England and the United States, circa 1790.

The final months of 1789 saw the birth of two countries, twins destined for rivalry. The United States of America formed as a union between the Southern states, stronger than the alliance under the Articles of Confederation but featuring a Bill of Rights, a unicameral House of Representatives in which all states were represented equally, limited federal powers, and firm protections for the states’ internal autonomy. Thomas Jefferson was elected the nation’s first President. 25 days after Jefferson’s first day in office, my own country came into being. The Federal Republic of New England elected President John Adams to lead their country into its first years of life, with a similar unicameral legislature and no Bill of Rights. I would like to point out that, from our lofty perspective in the future, it’s easy to decry this omission and predict the outcome. The early Federalists feared they would restrict the people’s rights by enumerating them, so that any potential loopholes could be exploited along with the population. Hamilton was not Iago. His actions didn’t stem from malice. It’s easy, comfortable even, to call him a villain and be done with it. The reality is always more complex than we’d like to believe. Hamilton did what he did for the same reason that a lot of people did. He was afraid his country would fall apart if he didn’t. All countries are forged from the virtue of our founding figures in the crucible of their sin.

George Washington said:"Example, whether it be good or bad, has a powerful influence."

Last edited: