At the suggestion of a friend, I have decided to work on and launch a timeline that forms the basis of the setting in Tragedy in Königsberg. The timeline commences at the Point of Divergence which is, in fact, the prologue of the novel.

I will try to update as often as I can, although regrettably this is unlikely to be as frequent as I would like.

Thank you for your interest.

-----------------------------------

Excerpt from A History of the Autumn War 1939-1940

The capitulation at Munich – The abrogation of that agreement – The political fallout resulting from that matter - The change of political leadership in France

Any examination of the Autumn War that purports to be honest or thorough, cannot be complete without first reviewing the Munich Agreement of September 1938. The Agreement authorised the annexation by Germany of the “Sudetenland” region of Czechoslovakia, an area bordering Germany and populated by some three and a half million ethnic Germans. The Agreement, which was greatly hoped to secure peace and cooperation in Europe, is now widely regarded by historians as an abject failure in diplomacy and appeasement. Its aftermath, namely the abrogation of the Agreement by Germany, lead indirectly to an increase in tensions across Europe and to the Autumn War of 1939.

Background

After the Anschluss of Austria in 1938, the German Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler, in pursuit of his policy of uniting all ethnic Germans under one nation, instructed the pro-Nazi leader Konrad Henlein of the Sudeten German Party (SdP) to step up a campaign an unreasonable demands for autonomy. This included terrorist attacks, coup attempts, and civil disobedience. Hitler’s instruction to Henlein was deliberately provocative, and he calculated that the Czechoslovakian government would be unable to meet the demands which would allow Germany to intervene in the crisis for their own purposes.

Recognising the precarious situation his country was in, Czechoslovakian President Edvard Beneš was prepared to grant considerable concessions but refused to grant complete autonomy. The SdP was under strict instructions from Hitler to not compromise, and throughout 1938 the violence in Czechoslovakia became more pronounced. Britain and France attempted to mediate and encouraged President Beneš to give in, but President Beneš refused – ordering a partial mobilisation of the army on 19 May 1938 in response to a possible German invasion.

The crisis escalated on 12 September 1938, where Hitler made a speech at a Nazi party rally in Nuremberg condemning Czechoslovakia. At this point Hitler had amassed over 750,000 German soldiers along the border of Czechoslovakia, and he threatened war to support the national self-determination of the German ethnic minority in the Sudetenland. War, it seemed, was inevitable and in an attempt to prevent violence British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain requested a personal meeting with Hitler to negotiate a solution. Chamberlain arrived in Germany on 15 September 1938 and held a three hour discussion with Hitler to no avail. Chamberlain returned to Britain to discuss the matter with his Cabinet, and held talks in London with the French Prime Minister Éduoard Daladier.

On 26 September 1938, Hitler issued an ultimatum to Czechoslovakia in a speech in Berlin. He gave Czechoslovakia until 28 September 1938 to capitulate to his demands for face an invasion.

Four hours prior to this deadline, the British government successfully convinced the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini to intervene in the crisis and request Hitler delay the ultimatum by 24 hours. Mussolini was also asked to attend a diplomatic conference in Germany to negotiate a peaceful solution to the crisis. Hitler agreed to this request and the conference was organised for 29 September 1938.

The Agreement was negotiated in conference at the German city of Munich between the leaders of Germany, France, Britain, and Italy. Czechoslovakia was in no way represented at the conference, and this lack of representation lead to bitter criticisms most particularly after the war. The Sudetenland was an important strategic portion of Czechoslovakia, as it contained a series of highly advanced defensive fortifications. It also possessed many heavy industrial facilities and was a source of considerable financial wealth with the numerous banking facilities.

After the conclusion of the negotiations, the Agreement was signed in the early hours of 30 September 1938. The Agreement authorised the annexation and incorporation of the Sudetenland directly into the Third Reich by 10 October. Czechoslovakia was advised by Britain and France that if it refused the terms of the Agreement, it would have to resist Germany alone. After briefly considering the situation, Czechoslovakia reluctantly agreed to the Agreement and, in exchange for their acceptance, Hitler promised that the Sudetenland was the extent of his ambitions in Czech.

Reactions to the Agreement - Germany

The Agreement was an unparalleled diplomatic success for Adolf Hitler, and he announced the results with the overwhelming backing of public opinion. However, privately Hitler was furious that he had been put into a position of acting as a peaceful politician. Hitler was personally scathing of Prime Minister Chamberlain and his reaction is vividly recorded by one of his staff:

But Hitler’s personal opinion aside, his success was generally popular in Germany. Even a group of conservative military officers, those who had seriously contemplated a military coup at that time, could not help but concede the enormous victory Hitler had obtained. The then Chief of the General Staff, General Ludwig Beck, had criticised Hitler in a series of memos that questioned the wisdom of starting a war. Beck, along with several other senior officers, planned to arrest Hitler the moment he ordered an invasion of Czechoslovakia. With the unexpected capitulation at Munich of Britain and France, these plans were shelved and it would be several years later, and in the middle of a disastrous war, that the Wehrmacht would finally step in and remove the Nazi Government.

Reactions to the Agreement - Britain

Interestingly, this popular feeling of support was not just isolated to Germany. The immediate domestic reaction to the agreement back in Britain and France was one of relief. Prime Minister Chamberlain was greeted enthusiastically on his return to Britain at the Heston Aerodrome where he famously proclaimed the “Peace for our time” speech. It is useful to record the sentiments expressed in his speech:

However, while the majority of the British population reacted positively initially, this was not a view shared universally. Future Prime Minister and then influential Conservative backbencher Winston Churchill denounced the Agreement as a failure of appeasement. He predicted, correctly as it eventuated, that it would not be enough to satisfy the territorial ambitions of Hitler for more than twelve months. Churchill was not alone in this criticism. The leader of the Liberal party Archibald Sinclair also bitterly criticised the Agreement and challenged the government to oppose Hitler. Although the leader of a mainstream political party, the Liberal party of 1939 was but a shadow of its former glory and held only 21 seats in a parliament of 640. Consequently, while undoubtedly the voices of Sinclair and Churchill were influential, they were overwhelmingly in the minority of parliamentary opinion while the Conservative and Labour parties remained committed to appeasement.

Reactions to the Agreement - France

Across the channel, the popular feeling in France was similar to Britain. Prime Minister Éduoard Daladier, on his return from the conference at Munich, was greeted by a crowd celebrating the Agreement. Unlike Chamberlain, Daladier had known the Munich Agreement would not be enough to satisfy Hitler's greed and he warned Chamberlain that “Today, it is the turn of Czechoslovakia. Tomorrow, it will be the turn of Poland and Romania.”[4]

Despite his misgivings he was unable to convince Chamberlain to oppose Hitler, and he acquiesced to the demands at Munich. On his return to Paris when he was greeted by a crowd with applause, he commented to his aide: “Ah, les cons (the fools)!”[5]

Reactions to the Agreement - Czechoslovakia

Only in Czechoslovakia could it be said that the popular reaction was overwhelmingly negative. The citizens of Prague bitterly denounced the capitulation of the west and were dismayed by the loss of their defensive fortifications. The remainder of the Czech state became utterly dependent on Germany, and its sovereignty was deeply threatened. More controversially, Poland had taken advantage of the political chaos by forcing the Czech Government to surrender the border town of Český Těšín. This uncomfortable fact would cause political difficulties after the Autumn War, when Poland and Czech were ostensibly close allies.

The abrogation of the Munich Agreement

Ultimately however, Poland's profit and the popular support generated in Britain and France were short lived. In March 1939, in direct violation of the agreement at Munich, Adolf Hitler summoned the President of Czechoslovakia, Emil Hácha, and demanded an immediate surrender of all remaining Czech territory. If President Hácha did not comply, Hitler would order the invasion and aerial destruction of Prague and other important cities. President Hácha, after suffering a heart attack during the confrontation, reluctantly capitulated his state to the demands of Germany.

On 15 March 1939, German troops crossed the border and seized the remaining territory of Czech without resistance or serious bloodshed. These regions were then directly incorporated into the Third Reich as the protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. The territory of Slovakia was made into a nominally independent puppet state under President Jozef Tiso.

The reaction to the occupation of Czechoslovakia

The reaction in Britain was immediate. Chamberlain was forced into a humiliating acknowledgement that he had been betrayed by Hitler and his credibility was greatly damaged. Hitler’s aggression was highly embarrassing for Chamberlain politically, and the scandal did much to boost the momentum of support for then backbencher Winston Churchill. The event crystallised opposition to the failed policy of appeasement, and from now on each of the principal political parties in Britain conceded that re-armament was now a necessity.

However it was across the English Channel where the political fallout was much more dramatic. French Prime Minister Éduoard Daladier came under bitter and sustained criticism for the failures at Munich, particularly when it was leaked that he did not think the Agreement was ever going to work. His most severe critics accused him of cowardice and weakness for following the lead of London despite his personal misgivings. For Daladier's part, he was in a difficult position politically. The right faction in his party did not think he was standing up to Hitler strongly enough: the capitulation at Munich the most dramatic example. On the other hand the left faction thought he was already being far too belligerent by beginning a process of modest rearmament across the defence forces. Daladier found the middle road increasingly difficult to navigate, and after the annexation of Czechoslovakia in March 1939, his political fortunes sunk very low.

Throughout this crisis, Daladier was undermined by his Foreign Minister Georges Bonnet. Bonnet was a firm pacifist and acknowledged leader of the peace faction. He was the strongest voice in Cabinet against any war with Germany. With respect to Czechoslovakia, he had opposed becoming involved at the very start, arguing it should be left to defend for itself. He was described by Winston Churchill as “the quintessence of defeatism.”[6] He was also a leadership rival to Daladier, and he had unsuccessfully tried to form a government in January 1938.

However, while Daladier largely kept Bonnet in Cabinet in part to prevent these leadership ambitions manifesting, after the German annexation of Czechoslovakia this position was no longer tenable. Daladier felt he could no longer rely on the loyalty or judgement of Bonnet. As a pacifist, Bonnet's presence in Cabinet undermined Daladier's ability to take a united stand against Germany.

The dismissal of Georges Bonnet

In a highly risky move, and against the advice of his political advisers, Daladier dismissed Bonnet from his post as Foreign Minister on 16 March 1939. Daladier's move was designed to shore up his political position in the party, and allow him to undertake a consistent approach which Bonnet's presence would prevent. Despite the calculations inherent in the move, it backfired disastrously for Daladier.[7]

In an interview with the famed British Thames Television production: Europe at War (1973), former political adviser to Prime Minister Daladier, Peter Boucher stated:

Bonnet, who controlled a significant portion of votes in the parliament, used his numbers to mount a challenge to Daladier's leadership. Even with all his supporters, he could not have hoped to prevail alone. Indeed, he recognised he would not have the necessary support to be Prime Minister and therefore he threw his support behind another candidate: Finance Minister Paul Reynaud.

The election of Paul Reynaud as Prime Minister of France

Paul Reynaud was a rising star in the parliament and had been appointed Finance Minister in late 1938. He had successfully seen off a number of challenges in his time, including militant union activity, and a successful means of curtailing inflation. His skillful management of the portfolio proved successful, with France’s industrial productivity increasing 25% from October 1938 to May 1939. He was also, most crucially, a bitter opponent of the appeasement strategy hithertho used by Daladier in dealing with Germany. Although publicly he remained a loyal Minister of the Government, privately he was highly critical of Daladier's leadership. Since the annexation of Czechoslovakia and the abrogation of the Munich Agreement, Reynaud's criticisms became more strident.

Reynaud's position in the party started to gain further support, and though he was widely seen as a rising star, he did not yet have his own independent level of support. In a secret meeting on 2 April 1939, Georges Bonnet and Paul Reynaud met to discuss a deal on the leadership. Together with Pierre Laval, former Prime Minister of two governments, they had the numbers to overtake Daladier.[9]

On 5 April 1939, these numbers were used to bring down Daladier’s government. Even with the extra votes, and despite the continuing grumbles and dissatisfaction with Daladier's leadership, the end result was extremely close. Paul Reynaud emerged as victorious with a margin of only one vote, making the showdown one of the closest votes in French political history.[10] Paul Reynaud was sworn in as Prime Minister the same day, electing to retain, for the most part, the same Cabinet. Pierre Laval was returned to Cabinet and sworn in as Finance Minister, Georges Bonnet was elevated to the Outer Ministry but did not obtain the Cabinet post he desired.

The ascension of Paul Reynaud as Prime Minister signalled a decisive turning point in the lead-up to the Autumn War. Reynaud brought a fresh approach to foreign policy, including a recognition of the true danger of Nazi Germany and a reluctance to follow London’s lead. He also quickly abandoned any idea of further concessions to Germany, and embarked on an ambitious program of re-armament and preparation. His leadership represented an end to the middle road approach unsuccessfully pursued by Daladier, but his divisive approach would cause controversy through the French army within a few months.[11]

------------------------

[1] A genuine quote from OTL.

[2] An amended quotation for TTL, based on Hitler's reported comments.

[3] A genuine quote from OTL.

[4] An paraphrased quotation for TTL, based on the sentiments expressed by Daladier.

[5] A genuine quote from OTL, as reported by Saint-John Perse.

[6] A genuine quote from OTL.

[7] This is the POD. In OTL Daladier kept Bonnet in Cabinet despite the mutual distrust between the two men. Daladier calculated it was safer to keep his rival close and under scrutiny than allow him to run a campaign of destabilisation. Undoubtedly this was a politically intelligent strategy. However, there is a better than even chance, in my view, that he could have gone the other way given the scandal of Munich and the humiliation it poured on France.

[8] A created quotation for TTL. Peter Boucher is a fictional character who has a minor appearance in Tragedy in Königsberg.

[9] Though Bonnet and Reynaud are of divergent political views, the capacity for human revenge always invites strange bedfellows - especially in politics. Pierre Laval, the supreme political opportunist, would be well placed to profit from such an arrangement and, in my view, is likely to have made himself available.

[10] Paul Reynaud prevailed by only one vote in OTL. I have replicated that result in TTL.

[11] In OTL Paul Reynaud became Prime Minister on 21 March 1940, after the fall of Poland and the end of the Winter War. Paul Reynaud was undoubtedly a courageous leader who saw the threat of Germany for what it was and he abandoned any idea of a truce or defensive war. Unfortunately, he was in power less than two months before the Battle of France, and was unable to greatly change things. In TTL, Paul Reynaud becomes Prime Minister almost 12 months earlier.

I will try to update as often as I can, although regrettably this is unlikely to be as frequent as I would like.

Thank you for your interest.

-----------------------------------

Excerpt from A History of the Autumn War 1939-1940

“The utmost my right honourable friend the Prime Minister has been able to secure by all his immense exertions, by all the great efforts and mobilisation which took place in this country, and by all the anguish and strain through which we have passed in this country, the utmost he has been able to gain for Czechoslovakia in the matters which were in dispute has been that the German dictator, instead of snatching the victuals from the table, has been content to have them served to him course by course.” –former Prime Minister, Rt Hon. Winston Churchill MP. 5 October 1938. House of Commons.[1]

The capitulation at Munich – The abrogation of that agreement – The political fallout resulting from that matter - The change of political leadership in France

Any examination of the Autumn War that purports to be honest or thorough, cannot be complete without first reviewing the Munich Agreement of September 1938. The Agreement authorised the annexation by Germany of the “Sudetenland” region of Czechoslovakia, an area bordering Germany and populated by some three and a half million ethnic Germans. The Agreement, which was greatly hoped to secure peace and cooperation in Europe, is now widely regarded by historians as an abject failure in diplomacy and appeasement. Its aftermath, namely the abrogation of the Agreement by Germany, lead indirectly to an increase in tensions across Europe and to the Autumn War of 1939.

Background

After the Anschluss of Austria in 1938, the German Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler, in pursuit of his policy of uniting all ethnic Germans under one nation, instructed the pro-Nazi leader Konrad Henlein of the Sudeten German Party (SdP) to step up a campaign an unreasonable demands for autonomy. This included terrorist attacks, coup attempts, and civil disobedience. Hitler’s instruction to Henlein was deliberately provocative, and he calculated that the Czechoslovakian government would be unable to meet the demands which would allow Germany to intervene in the crisis for their own purposes.

Recognising the precarious situation his country was in, Czechoslovakian President Edvard Beneš was prepared to grant considerable concessions but refused to grant complete autonomy. The SdP was under strict instructions from Hitler to not compromise, and throughout 1938 the violence in Czechoslovakia became more pronounced. Britain and France attempted to mediate and encouraged President Beneš to give in, but President Beneš refused – ordering a partial mobilisation of the army on 19 May 1938 in response to a possible German invasion.

The crisis escalated on 12 September 1938, where Hitler made a speech at a Nazi party rally in Nuremberg condemning Czechoslovakia. At this point Hitler had amassed over 750,000 German soldiers along the border of Czechoslovakia, and he threatened war to support the national self-determination of the German ethnic minority in the Sudetenland. War, it seemed, was inevitable and in an attempt to prevent violence British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain requested a personal meeting with Hitler to negotiate a solution. Chamberlain arrived in Germany on 15 September 1938 and held a three hour discussion with Hitler to no avail. Chamberlain returned to Britain to discuss the matter with his Cabinet, and held talks in London with the French Prime Minister Éduoard Daladier.

On 26 September 1938, Hitler issued an ultimatum to Czechoslovakia in a speech in Berlin. He gave Czechoslovakia until 28 September 1938 to capitulate to his demands for face an invasion.

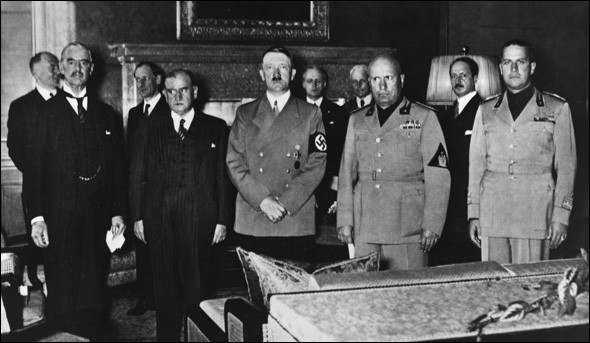

Four hours prior to this deadline, the British government successfully convinced the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini to intervene in the crisis and request Hitler delay the ultimatum by 24 hours. Mussolini was also asked to attend a diplomatic conference in Germany to negotiate a peaceful solution to the crisis. Hitler agreed to this request and the conference was organised for 29 September 1938.

The Agreement was negotiated in conference at the German city of Munich between the leaders of Germany, France, Britain, and Italy. Czechoslovakia was in no way represented at the conference, and this lack of representation lead to bitter criticisms most particularly after the war. The Sudetenland was an important strategic portion of Czechoslovakia, as it contained a series of highly advanced defensive fortifications. It also possessed many heavy industrial facilities and was a source of considerable financial wealth with the numerous banking facilities.

After the conclusion of the negotiations, the Agreement was signed in the early hours of 30 September 1938. The Agreement authorised the annexation and incorporation of the Sudetenland directly into the Third Reich by 10 October. Czechoslovakia was advised by Britain and France that if it refused the terms of the Agreement, it would have to resist Germany alone. After briefly considering the situation, Czechoslovakia reluctantly agreed to the Agreement and, in exchange for their acceptance, Hitler promised that the Sudetenland was the extent of his ambitions in Czech.

Reactions to the Agreement - Germany

The Agreement was an unparalleled diplomatic success for Adolf Hitler, and he announced the results with the overwhelming backing of public opinion. However, privately Hitler was furious that he had been put into a position of acting as a peaceful politician. Hitler was personally scathing of Prime Minister Chamberlain and his reaction is vividly recorded by one of his staff:

“He regarded him [Chamberlain] as an impertinent busybody who spoke the ridiculous jargon of an outmoded democracy. He further stated that if ever that silly old man comes interfering here again with his umbrella, I’ll kick him downstairs and jump on his stomach in front of the photographers.” –Erwin Scholz, Personal Staff at Hitler’s Berghoff. 2 February 1951. Interview with Der Spiegel. [2]

But Hitler’s personal opinion aside, his success was generally popular in Germany. Even a group of conservative military officers, those who had seriously contemplated a military coup at that time, could not help but concede the enormous victory Hitler had obtained. The then Chief of the General Staff, General Ludwig Beck, had criticised Hitler in a series of memos that questioned the wisdom of starting a war. Beck, along with several other senior officers, planned to arrest Hitler the moment he ordered an invasion of Czechoslovakia. With the unexpected capitulation at Munich of Britain and France, these plans were shelved and it would be several years later, and in the middle of a disastrous war, that the Wehrmacht would finally step in and remove the Nazi Government.

Reactions to the Agreement - Britain

Interestingly, this popular feeling of support was not just isolated to Germany. The immediate domestic reaction to the agreement back in Britain and France was one of relief. Prime Minister Chamberlain was greeted enthusiastically on his return to Britain at the Heston Aerodrome where he famously proclaimed the “Peace for our time” speech. It is useful to record the sentiments expressed in his speech:

“The settlement of the Czechoslovakian problem, which has now been achieved is, in my view, only the prelude to a larger settlement in which all Europe may find peace. This morning I had another talk with the German Chancellor, Herr Hitler, and here is the paper which bears his name upon it as well as mine. Some of you, perhaps, have already heard what it contains but I would just like to read it to you: ' ... We regard the agreement signed last night and the Anglo-German Naval Agreement as symbolic of the desire of our two peoples never to go to war with one another again.” –former Prime Minister, Rt Hon. Neville Chamberlain MP. 30 September 1938. On the announcement of the Munich Agreement.[3]

However, while the majority of the British population reacted positively initially, this was not a view shared universally. Future Prime Minister and then influential Conservative backbencher Winston Churchill denounced the Agreement as a failure of appeasement. He predicted, correctly as it eventuated, that it would not be enough to satisfy the territorial ambitions of Hitler for more than twelve months. Churchill was not alone in this criticism. The leader of the Liberal party Archibald Sinclair also bitterly criticised the Agreement and challenged the government to oppose Hitler. Although the leader of a mainstream political party, the Liberal party of 1939 was but a shadow of its former glory and held only 21 seats in a parliament of 640. Consequently, while undoubtedly the voices of Sinclair and Churchill were influential, they were overwhelmingly in the minority of parliamentary opinion while the Conservative and Labour parties remained committed to appeasement.

Reactions to the Agreement - France

Across the channel, the popular feeling in France was similar to Britain. Prime Minister Éduoard Daladier, on his return from the conference at Munich, was greeted by a crowd celebrating the Agreement. Unlike Chamberlain, Daladier had known the Munich Agreement would not be enough to satisfy Hitler's greed and he warned Chamberlain that “Today, it is the turn of Czechoslovakia. Tomorrow, it will be the turn of Poland and Romania.”[4]

Despite his misgivings he was unable to convince Chamberlain to oppose Hitler, and he acquiesced to the demands at Munich. On his return to Paris when he was greeted by a crowd with applause, he commented to his aide: “Ah, les cons (the fools)!”[5]

Reactions to the Agreement - Czechoslovakia

Only in Czechoslovakia could it be said that the popular reaction was overwhelmingly negative. The citizens of Prague bitterly denounced the capitulation of the west and were dismayed by the loss of their defensive fortifications. The remainder of the Czech state became utterly dependent on Germany, and its sovereignty was deeply threatened. More controversially, Poland had taken advantage of the political chaos by forcing the Czech Government to surrender the border town of Český Těšín. This uncomfortable fact would cause political difficulties after the Autumn War, when Poland and Czech were ostensibly close allies.

The abrogation of the Munich Agreement

Ultimately however, Poland's profit and the popular support generated in Britain and France were short lived. In March 1939, in direct violation of the agreement at Munich, Adolf Hitler summoned the President of Czechoslovakia, Emil Hácha, and demanded an immediate surrender of all remaining Czech territory. If President Hácha did not comply, Hitler would order the invasion and aerial destruction of Prague and other important cities. President Hácha, after suffering a heart attack during the confrontation, reluctantly capitulated his state to the demands of Germany.

On 15 March 1939, German troops crossed the border and seized the remaining territory of Czech without resistance or serious bloodshed. These regions were then directly incorporated into the Third Reich as the protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. The territory of Slovakia was made into a nominally independent puppet state under President Jozef Tiso.

The reaction to the occupation of Czechoslovakia

The reaction in Britain was immediate. Chamberlain was forced into a humiliating acknowledgement that he had been betrayed by Hitler and his credibility was greatly damaged. Hitler’s aggression was highly embarrassing for Chamberlain politically, and the scandal did much to boost the momentum of support for then backbencher Winston Churchill. The event crystallised opposition to the failed policy of appeasement, and from now on each of the principal political parties in Britain conceded that re-armament was now a necessity.

However it was across the English Channel where the political fallout was much more dramatic. French Prime Minister Éduoard Daladier came under bitter and sustained criticism for the failures at Munich, particularly when it was leaked that he did not think the Agreement was ever going to work. His most severe critics accused him of cowardice and weakness for following the lead of London despite his personal misgivings. For Daladier's part, he was in a difficult position politically. The right faction in his party did not think he was standing up to Hitler strongly enough: the capitulation at Munich the most dramatic example. On the other hand the left faction thought he was already being far too belligerent by beginning a process of modest rearmament across the defence forces. Daladier found the middle road increasingly difficult to navigate, and after the annexation of Czechoslovakia in March 1939, his political fortunes sunk very low.

Throughout this crisis, Daladier was undermined by his Foreign Minister Georges Bonnet. Bonnet was a firm pacifist and acknowledged leader of the peace faction. He was the strongest voice in Cabinet against any war with Germany. With respect to Czechoslovakia, he had opposed becoming involved at the very start, arguing it should be left to defend for itself. He was described by Winston Churchill as “the quintessence of defeatism.”[6] He was also a leadership rival to Daladier, and he had unsuccessfully tried to form a government in January 1938.

However, while Daladier largely kept Bonnet in Cabinet in part to prevent these leadership ambitions manifesting, after the German annexation of Czechoslovakia this position was no longer tenable. Daladier felt he could no longer rely on the loyalty or judgement of Bonnet. As a pacifist, Bonnet's presence in Cabinet undermined Daladier's ability to take a united stand against Germany.

The dismissal of Georges Bonnet

In a highly risky move, and against the advice of his political advisers, Daladier dismissed Bonnet from his post as Foreign Minister on 16 March 1939. Daladier's move was designed to shore up his political position in the party, and allow him to undertake a consistent approach which Bonnet's presence would prevent. Despite the calculations inherent in the move, it backfired disastrously for Daladier.[7]

In an interview with the famed British Thames Television production: Europe at War (1973), former political adviser to Prime Minister Daladier, Peter Boucher stated:

“I told him [Daladier] quite simply that I could not, to a sufficient degree, guarantee his victory in a leadership challenge. It was my view then, and it still is now, that if Bonnet had remained in Cabinet it would have been Daladier that led France to war – not Reynaud.” –former political adviser, Peter Boucher. 31 October 1973. In “Europe at War.”[8]

Bonnet, who controlled a significant portion of votes in the parliament, used his numbers to mount a challenge to Daladier's leadership. Even with all his supporters, he could not have hoped to prevail alone. Indeed, he recognised he would not have the necessary support to be Prime Minister and therefore he threw his support behind another candidate: Finance Minister Paul Reynaud.

The election of Paul Reynaud as Prime Minister of France

Paul Reynaud was a rising star in the parliament and had been appointed Finance Minister in late 1938. He had successfully seen off a number of challenges in his time, including militant union activity, and a successful means of curtailing inflation. His skillful management of the portfolio proved successful, with France’s industrial productivity increasing 25% from October 1938 to May 1939. He was also, most crucially, a bitter opponent of the appeasement strategy hithertho used by Daladier in dealing with Germany. Although publicly he remained a loyal Minister of the Government, privately he was highly critical of Daladier's leadership. Since the annexation of Czechoslovakia and the abrogation of the Munich Agreement, Reynaud's criticisms became more strident.

Reynaud's position in the party started to gain further support, and though he was widely seen as a rising star, he did not yet have his own independent level of support. In a secret meeting on 2 April 1939, Georges Bonnet and Paul Reynaud met to discuss a deal on the leadership. Together with Pierre Laval, former Prime Minister of two governments, they had the numbers to overtake Daladier.[9]

On 5 April 1939, these numbers were used to bring down Daladier’s government. Even with the extra votes, and despite the continuing grumbles and dissatisfaction with Daladier's leadership, the end result was extremely close. Paul Reynaud emerged as victorious with a margin of only one vote, making the showdown one of the closest votes in French political history.[10] Paul Reynaud was sworn in as Prime Minister the same day, electing to retain, for the most part, the same Cabinet. Pierre Laval was returned to Cabinet and sworn in as Finance Minister, Georges Bonnet was elevated to the Outer Ministry but did not obtain the Cabinet post he desired.

The ascension of Paul Reynaud as Prime Minister signalled a decisive turning point in the lead-up to the Autumn War. Reynaud brought a fresh approach to foreign policy, including a recognition of the true danger of Nazi Germany and a reluctance to follow London’s lead. He also quickly abandoned any idea of further concessions to Germany, and embarked on an ambitious program of re-armament and preparation. His leadership represented an end to the middle road approach unsuccessfully pursued by Daladier, but his divisive approach would cause controversy through the French army within a few months.[11]

------------------------

[1] A genuine quote from OTL.

[2] An amended quotation for TTL, based on Hitler's reported comments.

[3] A genuine quote from OTL.

[4] An paraphrased quotation for TTL, based on the sentiments expressed by Daladier.

[5] A genuine quote from OTL, as reported by Saint-John Perse.

[6] A genuine quote from OTL.

[7] This is the POD. In OTL Daladier kept Bonnet in Cabinet despite the mutual distrust between the two men. Daladier calculated it was safer to keep his rival close and under scrutiny than allow him to run a campaign of destabilisation. Undoubtedly this was a politically intelligent strategy. However, there is a better than even chance, in my view, that he could have gone the other way given the scandal of Munich and the humiliation it poured on France.

[8] A created quotation for TTL. Peter Boucher is a fictional character who has a minor appearance in Tragedy in Königsberg.

[9] Though Bonnet and Reynaud are of divergent political views, the capacity for human revenge always invites strange bedfellows - especially in politics. Pierre Laval, the supreme political opportunist, would be well placed to profit from such an arrangement and, in my view, is likely to have made himself available.

[10] Paul Reynaud prevailed by only one vote in OTL. I have replicated that result in TTL.

[11] In OTL Paul Reynaud became Prime Minister on 21 March 1940, after the fall of Poland and the end of the Winter War. Paul Reynaud was undoubtedly a courageous leader who saw the threat of Germany for what it was and he abandoned any idea of a truce or defensive war. Unfortunately, he was in power less than two months before the Battle of France, and was unable to greatly change things. In TTL, Paul Reynaud becomes Prime Minister almost 12 months earlier.

Last edited: